Not everyone communicates uuing speech. Some people understand everything around them but can’t speak clearly. Others speak a few words, but it’s not enough to express everything they want. In many cases, this can be due to a developmental delay, disability, brain injury, or a progressive condition. When speech doesn’t meet a person’s daily communication needs, they might benefit from something called AAC.

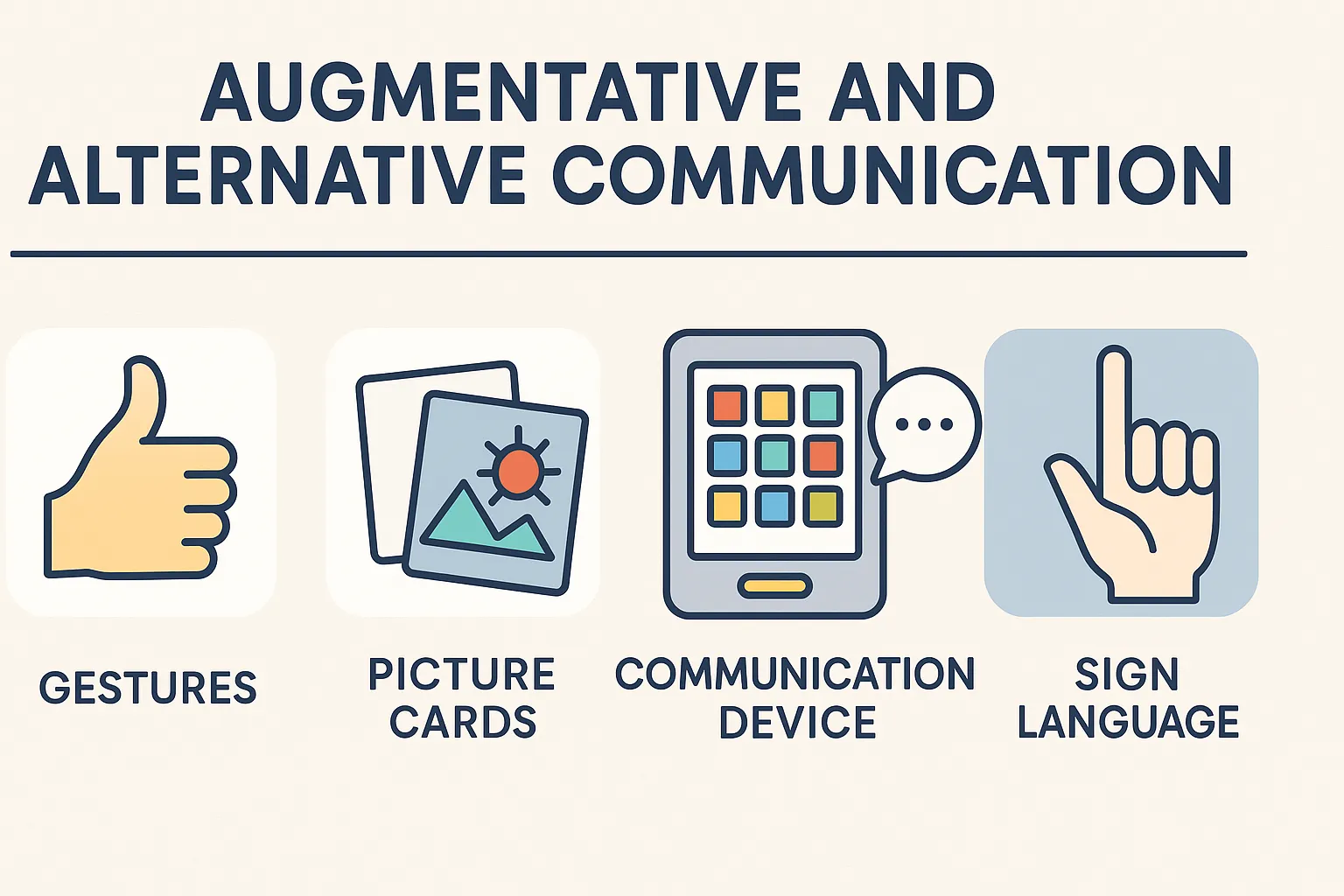

AAC stands for Augmentative and Alternative Communication. It’s a broad term that includes all the ways someone can communicate if they have difficulty with spoken language. It can be temporary—used during recovery from surgery, for example—or it can become a person’s main way of communicating throughout life.

AAC can be as simple as a nod or pointing to a picture, or as advanced as using a tablet that talks. It’s not one-size-fits-all. What matters is that the person has a reliable way to express their needs, make choices, and be part of everyday conversations.

What is AAC?

AAC includes any method of communication that helps someone express themselves when speaking is hard. The two key ideas in AAC are:

- Augmentative: tools that add to existing speech, helping make it clearer or easier to understand

- Alternative: tools that replace speech when someone can’t talk at all

It’s important to understand AAC isn’t a single device or system. It’s a collection of different methods—some simple, some complex—that can be matched to the person’s physical ability, age, environment, and communication needs.

Examples of AAC include:

- Pointing to pictures to request food

- Using a voice-output app to say a sentence

- Typing on a device that speaks the words aloud

- Signing “more” or “toilet” during a routine

AAC doesn’t delay speech development. In fact, research shows it supports it. Giving someone a clear, consistent way to communicate reduces frustration and helps them feel heard. Over time, this can support confidence, social connection, and learning.

AAC might be used in every interaction or only in specific settings. Some people use speech and AAC together, switching between them as needed. The goal isn’t to replace speech—it’s to make sure communication always happens, no matter the method.

Who uses AAC?

AAC can be used by children, teens, and adults who struggle to communicate using speech alone. This might include people who are non-speaking, speak very little, or whose speech is difficult to understand. Some people use AAC for life, while others use it for a short period during recovery or development.

Common reasons someone might benefit from AAC include:

- Developmental delay or global developmental delay

- Autism, especially when spoken language is limited or delayed

- Cerebral palsy, where muscle control affects speech clarity

- Down syndrome, particularly when expressive language is affected

- Stroke or brain injury, leading to partial or full loss of speech

- Progressive neurological conditions like motor neurone disease (MND), multiple sclerosis (MS), or Parkinson’s

- Temporary speech loss, such as after surgery on the throat or jaw

It’s also important to note that AAC is not only for people who don’t speak at all. Many people who use AAC can speak a few words or short sentences, but need extra support to express full thoughts, ask questions, or participate in longer conversations.

AAC helps ensure people can take part in daily routines, build relationships, and have control over what happens around them. The earlier it’s introduced, the more benefit it can provide, especially when combined with therapy and daily use across different environments.

Types of AAC

AAC systems are generally grouped into two categories: unaided (body-based) and aided (tool-based). Each category has its own strengths and challenges, and many people use a mix of both depending on the situation.

Unaided AAC

This means the person communicates without any tools—just using their body.

Examples include:

- Hand gestures like pointing, waving, or giving a thumbs-up

- Facial expressions such as smiling, frowning, or raising eyebrows

- Body posture, nodding, or head shaking

- Sign language or keyword signing (e.g. AUSLAN signs)

Pros:

- Always available—no setup or equipment needed

- Can be very fast for familiar people

- Helps develop foundational communication skills

Limitations:

- Can be misunderstood by unfamiliar people

- Not suitable if the person has limited motor skills

- Has limits when trying to express complex ideas

Aided AAC

These involve using tools or equipment to help communicate.

Low-tech AAC includes:

- Picture exchange cards (e.g. PECS)

- Communication books or boards

- Visual schedules

- Spelling or alphabet boards

Mid-tech AAC includes:

- Simple speech buttons with one or a few recorded messages

- Battery-operated devices that play sounds or phrases

High-tech AAC includes:

- Speech-generating devices (SGDs) with dynamic displays

- Tablets or iPads with AAC apps (e.g. Proloquo2Go, TD Snap)

- Eye-gaze or switch-based systems for people with very limited movement

Choosing the right type of AAC depends on:

- Physical ability (e.g. hand control, eye movement)

- Literacy level

- Language comprehension

- Environment (school, home, day program)

- Support available for setup and training

AAC tools can be trialled, changed, and updated as the person grows and their needs evolve.

How AAC supports everyday life

AAC isn’t just for clinical settings—it has a real impact on everyday life. It opens the door to choice, connection, learning, and independence. Whether it’s asking for breakfast or saying “I don’t like that,” communication affects nearly every part of daily living.

Here’s how AAC can make a difference:

- Supports independence: People can express basic needs, make choices, and participate in daily decisions. Instead of others guessing, AAC helps the person speak for themselves.

- Reduces frustration: When someone can’t communicate, it often leads to distress or behaviour challenges. AAC gives a clear, reliable way to be understood.

- Improves learning: In school settings, AAC supports children to answer questions, follow instructions, and engage with peers. It levels the playing field for communication-based tasks.

- Encourages social interaction: AAC allows people to say hello, tell a joke, or share an idea. This builds friendships and reduces isolation.

- Helps manage emotions: Some AAC systems include feelings boards or visual supports that let the person express how they feel, even during meltdowns or shutdowns.

- Builds confidence: When communication works, people are more willing to try new things, explore environments, and speak up.

With consistent use and support from carers, therapists, or educators, AAC becomes part of daily routines—and communication becomes easier, faster, and more natural.

Common misconceptions about AAC

AAC is often misunderstood, especially by those new to disability or communication support. Families may worry that introducing AAC will slow speech development or make things more complicated. The opposite is usually true.

Let’s clear up some common myths:

- “AAC will stop my child from talking.”Research shows AAC supports spoken language. Many children start to talk more after using AAC because they’re under less pressure and more successful at being understood.

- “AAC is only for people who can’t talk at all.”AAC also helps people who speak a few words, speak unclearly, or struggle to express full sentences. It adds to speech, not replaces it.

- “AAC is too hard for young children or people with intellectual disability.”AAC can be used by toddlers and people with limited cognitive ability. The key is to match the tool to the person—simple picture boards can be just as powerful as high-tech devices when used consistently.

- “They don’t need AAC because they can say a few words.”Having some speech doesn’t mean communication is easy. If speech breaks down in stressful, fast-moving, or unfamiliar situations, AAC can fill the gap and reduce confusion.

Supporting AAC means giving someone every chance to be heard and to understand others. It’s never about giving up—it’s about opening possibilities.

Getting started with AAC

Starting AAC begins with understanding the person’s communication needs. A qualified speech pathologist plays a key role in assessing what the person can do, what they need support with, and which tools might help.

Key steps in getting started include:

- Assessment: The speech therapist observes the person’s current communication methods, daily routines, physical ability, and comprehension

- Trial: AAC tools are trialled to see what works—this could include printed visuals, apps, or devices

- Training: Support is given to the person, family, and staff so everyone knows how to use the AAC system

- Integration: AAC is built into daily routines like mealtimes, play, outings, and learning

- Review: The system is adjusted as the person grows or their needs change

AAC can be funded through the NDIS under categories like Assistive Technology and Capacity Building – Improved Daily Living. In most cases, a formal assessment and quote are required. Families and carers can speak with their therapy team or support coordinator to begin this process.

The most successful AAC setups are those that are well-supported, used consistently, and treated as part of normal communication—not as a separate activity.

Conclusion

AAC gives people a voice, especially when speech doesn’t meet their needs. It helps them connect, express, and participate in ways that are meaningful to them. Whether it’s pointing to a picture, tapping a button, or using a speech app, AAC can turn confusion into clarity.

There is no perfect age to begin AAC—what matters is recognising when communication is limited and taking steps to support it. With the right setup, ongoing support, and people who are willing to learn alongside, AAC can become a natural part of everyday life.

If someone you support struggles to communicate, AAC is worth exploring. It doesn’t need to be high-tech or complicated—it just needs to work.